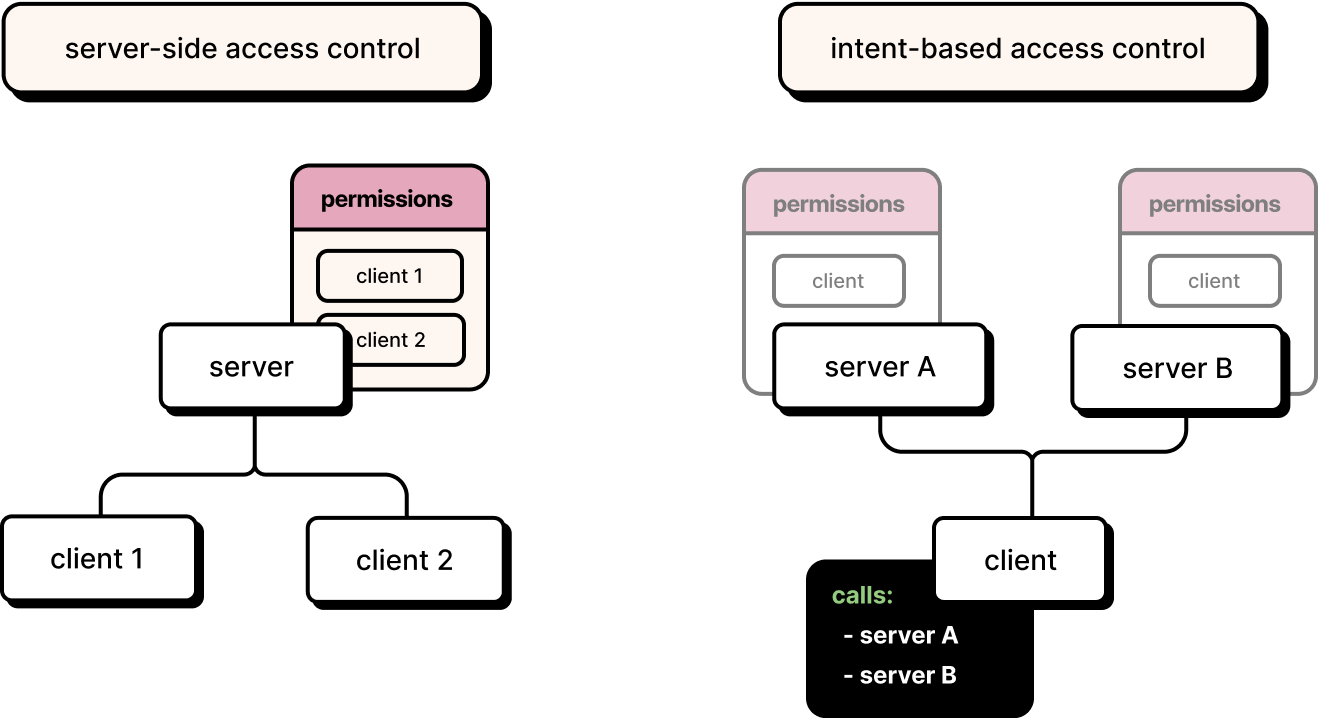

IBAC: Intent-based access control

At Otterize, we believe workload IAM should become not only easy but actually transparent to developers. We believe that access should not only be self-serve — that it should happen without needing to go through any extra steps beyond what developers are already doing. And we believe that access control enforcement should be completely decoupled from the functional development of the software: that as the organization improves its security and compliance posture, developers should not need to revisit their working code.

These are the principles of intent-based access control (IBAC), a modern, declarative approach to granting access automatically, responsibly, and scalably. The developer simply declares, in a ClientIntents custom resource alongside their code, what other services the code intends to call. If the code passes review, so does its intents, and access is granted automatically to make those calls, regardless of the type of call, the target infrastructure and location, and the enforcement mechanism. Credentials for declared access are automatically managed and supplied to the service for use in their code, if needed. Any undeclared access is automatically blocked.

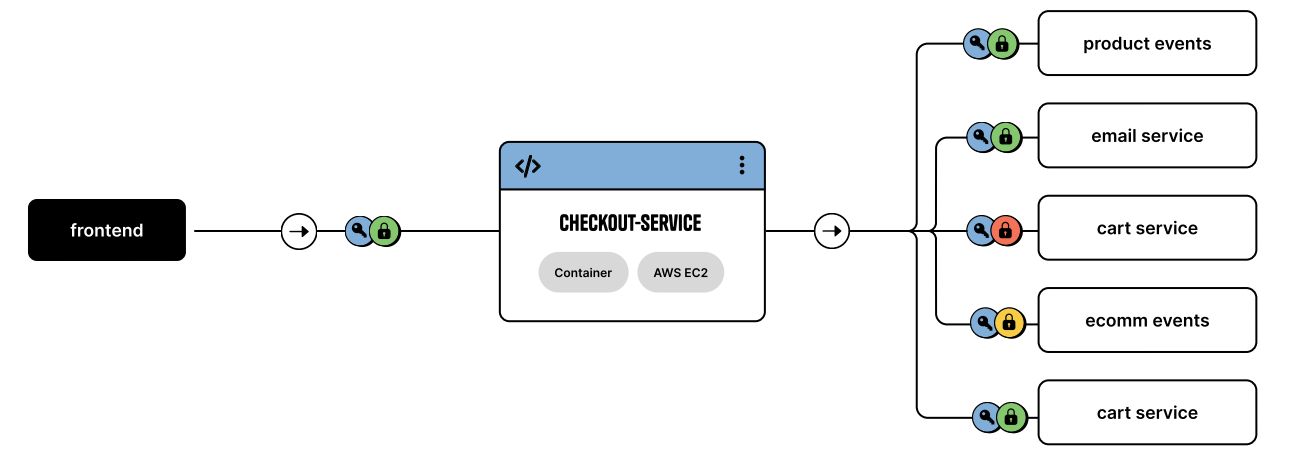

Here is an example of the client intents file for the checkoutservice.

It declares that it will call the emailservice, the orderservice, and the ecomm-events Kafka service.

It also provides more granular information for some of the calls, which you can optionally specify, like HTTPResources:

apiVersion: k8s.otterize.com/v1alpha3

kind: ClientIntents

metadata:

name: checkoutservice

spec:

service:

name: checkoutservice

calls:

- name: emailservice

type: http

- name: orderservice

type: http

HTTPResources:

- path: /orders/*

methods: [ get, post ]

- name: ecomm-events

type: kafka

kafkaTopics:

- name: orders

operations: [ produce ]

Intent-based access control realizes shift-left for access control. The necessary access is defined by the developer themselves declaring, when the code is created, what calls will be made. Nobody knows better than them what their code needs. And those declarations, living in source control as client intents files along with the code, stay in sync with the code — as opposed to access permissions that live elsewhere, e.g. on a server, where they’re likely to get stale rapidly. Intents are approved along with the code: if it makes sense to approve the code that makes the calls, it should make sense to approve access to what’s being called.

Developers might even think about IBAC as “SSO for services”: with just one intents file, they can securely access any target service, running on any technology, on any infrastructure and in any environment. And when new services, technologies and infrastructures are added, or new security or compliance requirements arise, developers don’t have to change what they do at all.

Intent-based access control is:

- Responsible: Intents files are managed with the code, go through the same approvals process, and can be augmented by rules before access is automatically granted.

- Scalable: The intents file of a service just declares the calls the service needs to make as a client of other services, because this is what the developer knows when building the service (rather than what will need to call their service). When the service changes, its intents file is updated. IBAC then uses the information in all the client intents files to derive the authorization rules on the server side, without the server team needing to constantly update access controls.

Ideally, IBAC is also:

- Automatic: Once client intents are known, server permissions are knowable and therefore automatable.

Automating IBAC

Otterize automates IBAC by integrating with existing infrastructures and enforcement points (Kafka ACLs, K8s network policies, AWS security groups, API gateways, etc.) to configure their built-in enforcement mechanisms.

The result is the least possible overhead and friction:

- platform engineers can completely eliminate the access control friction for their devs, without needing to field access requests or roll their own automations for every new technology;

- developers get a standard way to acquire access to any service without knowing anything about security mechanisms and without changing anything about their current development processes;

- architects gain a unified, virtual access control layer without embedding any new technology layers in their stack;

- security and compliance benefit from a zero-trust network of services baked into the system design, fully visible, provable, dynamic, and controllable through automation rules.

The collection of intents across the various environments form a semantic access graph that captures the full intent of the code. Automation rules then act on that intent layer of the access graph, resulting in some intents turning into access grants while other intents await approval or are rejected; that overlay of intent states forms another layer of the access graph: the target access layer. Finally, the target access state of each server are compared with the actual state of the enforcement points available on that server: one server might only be protected by Kubernetes network policies so it cannot control fine-grained access, only allow/deny to the caller; another server might be a Kafka server with its built-in enforcement of operation-level ACLs on any topic. Otterize, as an IBAC platform, will configure the available enforcement points to reflect as closely as possible the desired access state, but in any case the actual access state forms another layer of the access graph: the enforced access layer.

To implement IBAC across heterogeneous environments, IBAC must also solve for the problem of heterogeneous service identities. (Intent-based access control incorporates identity-based access control.) Since IBAC does not require developers to know about identity mechanisms any more than about authorization mechanisms, there is the requirement to bridge the identity of the client service to identities recognized by the target service’s infrastructures and enforcement mechanisms. Otterize builds in identity bridging mechanisms into all its integrations.

IBAC and security

Security controls that don't get implemented don't help. By shifting-left the access controls - — capturing the intent at design time, streamlining for developers the access to secured services, integrating access reviews into existing code review processes, and automating access control configuration at deploy time — IBAC drives adoption of security controls and a zero-trust architecture within the engineering team. It perhaps goes without saying that if secure access is hard, there’s a tendency to avoid it -- so when secure access becomes easy, it's also more prevalent, leading to fewer security issues and compliance friction.

Intent-based access control doesn't fly in the face of organizational security policies, and it certainly doesn't replace them. IBAC aligns access controls with the needs of the organization. It captures and makes explicit the intents of developers and their code, enables processes for acting on those intents to allow or deny access, and makes explicit the enforcement that's actually put in place. One org might decide that it's best to automatically approve all intents once they undergo code review and apply them to a staging environment so they can be tested, but require explicit SecOps approval on any new intent before it's applied to production. Another org might decide to require approvals only on some servers (i.e. intents targeted at those servers), and to track them by filing issues against the server teams' ticketing system. And a third org might decide to enforce access controls on certain servers in staging to make sure intents are declared, but operate for some time in shadow mode in production until they get comfortable that the controls work right before enforcing them.